The skinny on gutbug-transplanted obesity

For centuries, mankind has looked into the vast skies and wondered “are we alone?” We still don’t know. But if we turn our gaze inwards, towards our own bodies, then the answer is a definitive “NO!”

100 trillion microbugs thrive in our intestines, forming complex communities – called “microbiota”- that live with us in symbiosis. (The word “microbiome” that you often hear describes the set of GENES that a particular microbiota has). Our gut bugs munch on the foodstuffs that we inadvertently share with them, not only helping us digest carbohydrates and ferment fibre, but also heavily influencing our metabolism. In fact, depending on the composition of your microbiota, they may influence your risk of Type II diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and mood.

They may even help shape your waistline.

Numerous studies have shown that obese and lean people harbour divergent populations of gut microbes; when obese people lose weight on either a fat- or carbohydrate-restricted diet, their gut bug populations gradually shift to that of a lean person’s. A recent study surveying 292 Danes found that obese people have fewer and less diverse gut bacteria populations, constituting an impoverished state that correlated with increased inflammation and risk of future weight gain.

But these observational studies cannot tell us which came first: obesity or obesity-associated microbiota? In other words, can gut microbes CAUSE obesity?

Ridaura VK et al (2013). Gut microbiota from twins discordant for obesity modulate metabolism in mice. Science doi:10.1126/science.1241214.

Researchers recruited four pairs of female human twins whom drastically differed in body composition (BMI difference >=5.5) and collected a sample of their microbiota. If you’re imagining long cartoonish needles, think again: since microbes heavily populate the large intestine, many hitch a hike with foodstuff and eventually gets shuffled out as poop – ready for collection. Researchers then transplanted the fecal samples into lean germ-free mice, fed them a standard low-fat diet and waited for the bugs to colonize the mice’s virgin guts.

15 days later, the bodies of recipient mice morphed into their human donor’s composition and shape. As you can see above, while “lean” bug-receiving mice (left) retained their body fat levels, those getting “obese” bugs dramatically packed on the squishy pounds (right). When researchers inoculated a new group of mice with “pure” bacteria cultured from the original fecal samples, the same divergence in body fat gain was observed.

Here's a nifty summary. Source: Science 341 (6150): 1069-1070

The few extra pounds weren’t the big problem – mice receiving “obese” bugs also started metabolizing amino acids in a way often seen in insulin-resistant humans, suggesting that their metabolisms were becoming compromised.

The researchers next wondered if these negative changes in body composition could be prevented with a healthy dose of “lean” bugs in an epic “battle of the microbes”. Following “obese” germ-transplants, researchers fed the mice with standard low-fat chow and waited until the bugs stabilized in their guts. Before recipient mice showed apparent signs of weight gain, researchers dropped “lean” bug-inoculated mice into their home cages. Since mice regularly ate each other’s feces, housing the two together should hypothetically result in a hearty mingling of each other’s gut bugs.

Or so it seemed. Although the microbiota of “obese”-germ mice was infiltrated with that of “lean”-germ mice, the swap was a one-way street – “lean”-germ mice retained their original microbiota, as well as their svelte physique (red bar in the graph below). Co-housing saved “obese”-germ mice from their rotund fate; their fat gain dramatically slowed (Ob-ch, empty blue bar), as compared when housed alone (Ob-Ob, solid blue bar).

Why this one-directional infiltration? Careful genomic analysis revealed the answer may be population diversity: because an obese germ community is less diverse than a lean one, it leaves many empty “niches” in the intestines – prime real estate for “lean” bacteria to move in. The fiercest invaders were from the Bacteroidetes family, whose overrepresentation in gut flora has previously been associated with leanness in mice.

If “lean” microbes tend to wipe out and replace “obese” ones, why is it that we have an obesity problem instead of a “lean” epidemic (I wish!)? The answer may partially lie in – you’ve probably guessed it - diet. In the above experiments, all mice were fed the same low-fat high-fibre diet, regardless of the type of microbiota received. To see if diet changes anything, the authors cooked up two human diet based recipes, one high in fruits and vegetables but low in saturated fat, and one with the opposite composition.

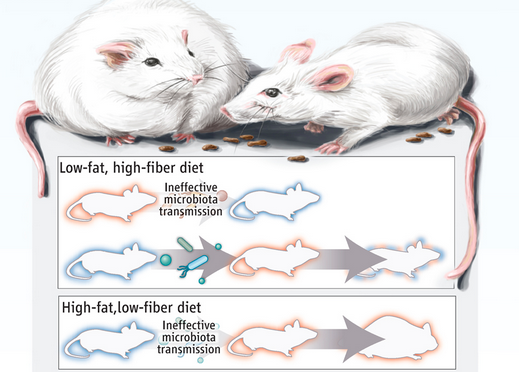

When “obese”-germ mice gobbled the low-fat high-veg chow, they still gained more weight and showed signs of mild glucose intolerance, which was once again canceled by co-housing with their “lean”-germ peers . However, on a diet high in fat but low in veg, “obese”-germ mice rapidly gained fat mass, regardless of whom they were housed with. In other words, a high fat diet barricaded any attempts that the “lean” germs might have made to invade the “obese” germ community.

Why is this the case? Bacteroidetes, the most successful invaders, are experts at breaking down dietary fibres into short-chain fatty acids, which can be used by the host as energy. Previous studies have shown – somewhat paradoxically – that these fatty acids promote leanness by inhibiting fat accumulation, increasing metabolism and enhancing the level of hormones that promote feelings of fullness. On a high-fat low-veg diet, the Bacteroidetes lacked the magic ingredient to work with and couldn’t establish themselves in the “obese”-germ mice. Any weight management benefits died off with the bacteria. The difference between high- and low-fat diet was only 11% by weight; it’s interesting to note that increasing fibre (as opposed to decreasing fat) may be more helpful in sculpting your waistline. I’d love to know what would’ve happened if the mice were fed a high-fat, high-fibre diet; would weight gain still be prevented by "lean" microbe transfer?

Summary #2. Source: Science 341 (6150): 1069-1070

So how relevant are the findings for us humans? Results from studies looking at Bacteroidetes in humans have been mixed – they seem to increase in obese individuals in some studies. So the jury’s still out there. What I'm wondering is whether transplanting “obese” microbiota into ALREADY obese mice can REVERSE their weight gain. If so, it’s certainly possible to isolate a few important “lean” strains and develop them into probiotics with anti-obesity powers. That is, if you watch your diet.

In the meantime, I’ll still stick to the good old mantra: eat less, move more.

Ridaura VK, Faith JJ, Rey FE, Cheng J, Duncan AE, Kau AL, Griffin NW, Lombard V, Henrissat B, Bain JR, Muehlbauer MJ, Ilkayeva O, Semenkovich CF, Funai K, Hayashi DK, Lyle BJ, Martini MC, Ursell LK, Clemente JC, Van Treuren W, Walters WA, Knight R, Newgard CB, Heath AC, & Gordon JI (2013). Gut microbiota from twins discordant for obesity modulate metabolism in mice. Science, 341 (6150) PMID: 24009397