Growing Human Organs In Pigs? Don't Get Too Excited Just Yet

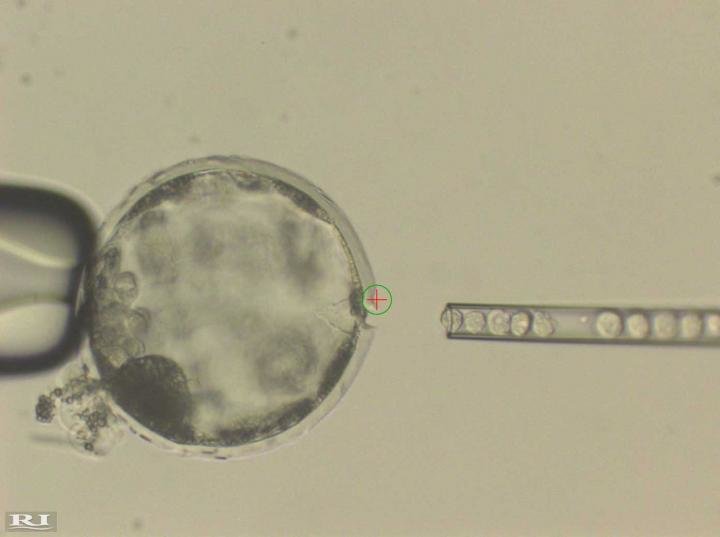

Pig embryo with human cells. Your holy f** image of the day. Credit: Courtesy of Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte

Last week, scientists at the Salk Institute announced that they had successfully created human-pig embryos.

Why would anyone even attempt something like that?

There's actually quite a lot of value in human-animal chimeras. In a nutshell, they may provide critical insights into early human development and may eventually provide functional tissues and organs that can be transplanted into those who need them.

In other words, animals - especially pigs, which are similar in size to humans - could supply us with human organs, and solve the issue of organ shortage once and for all.

This photograph shows injection of human cells into a pig embryo. A laser beam (green circle with a red cross inside) was used to open up the pig cell membrane, so that a human cells can be injected straight in using a thin needle. Science is cray!

Credit: Courtesy of Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte

The problem is getting human cells to adapt to an animal embryo is harder than expected. For example, the Salk scientists had no trouble introducing rat stem cells into mouse embryos. When they deleted a gene that's critical for forming a mouse pancreas, the rat stem cells stepped up and filled in that gap - since they still have the "pancreas gene", the rat cells ended up filling in where mouse cells couldn't. The chimeric mouse grew to a healthy adult age, with a "rat pancreas", in a manner of speaking.

So far so good. But when the scientists tried the same trick on human cells and pig embryos, the chimeric embryos were scrawny and unhealthy, and most of the human cells didn't survive. Although the chimeras were only allowed to develop for 3-4 weeks due to ethical concerns, it became fairly obvious that the embryos might have had a tough time surviving to full term. Even if they had, they might've not carried the human organs that scientists were hoping for.

The results are a bit of a whoomp-whoomp to people hoping to harvest human organs from animals anytime soon. But they also tell us that the idea is feasible, although there's a lot more optimizing to do. Recent advances in genetic editing (namely, CRISPR and its newer renditions) may help, but ultimately we may need to better understand the intricate dance that stem cells undertake during embryonic development - and how the dances differ between species - before we can start successfully remixing them together.

(To stretch out that analogy just a bit further, a big problem right now is that human and pig stem cells can't beat-match: their development trajectories occur at different speeds, so trying to mix the two together can throw off both tracks.)

***

Last June I first caught wind of the story and wrote about it for Singularity Hub here. Follow the link if you'd like more details into the history and science behind human-animal chimeras, as well as all the ethical concerns associated with such a radical idea.